Kim Kardashian & Kylie Jenner, @kimkardashian Instagram profile, 2019.

Kim Kardashian & Kylie Jenner, @kimkardashian Instagram profile, 2019. Still from Guy Debord & Brigitte Cornand: Guy Debord, son art et son temps, 1994.

Still from Guy Debord & Brigitte Cornand: Guy Debord, son art et son temps, 1994.

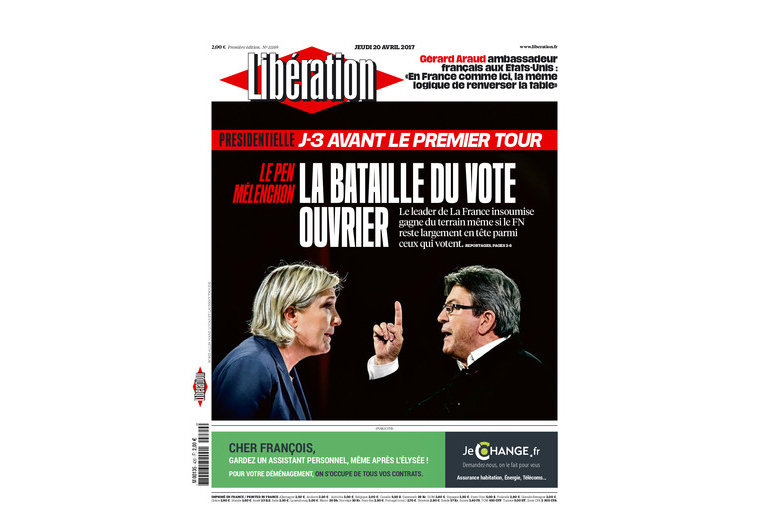

The cover of Libération, 20. April 2017.

The cover of Libération, 20. April 2017.

Still from I Got Surgery to Look Like My Snapchat and Facetune Selfies, Vice, 2019.

Still from I Got Surgery to Look Like My Snapchat and Facetune Selfies, Vice, 2019.

“My life is the construction of bridges. I am the pontoon between the glacial period and the Commune”.

Heiner Müller: Der Bau, 1980

We live in the spectacle, without a proletariat. When Guy Debord coined the notion of the society of the spectacle in the early 1960s, he could of course not envision the image machines we have at our disposal today. That’s probably for the best. Debord killed himself in 1994 shooting himself in the head. Just before doing that he made one last film called “Guy Debord: His Art and his Time” (video link). The film starts with a television clip of critics sitting around a table in a television studio discussing and trashing Debord’s Comments on the Society of the Spectacle. The scene goes on for several minutes with one critic, Franz-Olivier Giesbert, journalist, TV-presenter and opinionator in one despicable mix, arguing that Debord is apparently unaware of the democratic gains achieved everywhere on the planet. The scene ends with the six critics agreeing that the book advances a conspiratorial thesis and legitimizes violence. Unlike in his other films where voice-over commentary exposes and critiques the images shown here Debord leaves the stupidity of television debate to speak for itself. Debord was a great analyst of symbol management and the scene is an apt depiction of the ability of the established institutions to nullify attempts in political thinking transforming everything into opinions and soundbites. It was already really late, the cards were stacked massively against revolutionary critique.

Debord was from the very start busy defending himself. Desperately trying to postpone the inevitable commodification of his negativity. It can come off as pretty obnoxious, Debord endlessly smoothing his imago, but it was necessary in order to prevent recuperation, trying to defer it or at least point elsewhere, beyond the spectacle commodity economy. Because Debord knew that beneath the spectacle the proletariat was still there. That there was a logic to history, that the imbecile critics were wrong. We are sadly bereft of that certainty today.

When Debord wrote The Society of the Spectacle he was confronted with film, radio and television and the early advertising industry that was selling the new commodity culture of the post-war economic boom in Western Europe. The political-economic compromise of the post-war period paved the way for access to better housing, education, culture and a steady paycheck. In exchange, the local working-class ditched internationalism and forgot about the wretched of the earth. Debord and the Situationist had a keen awareness of the enormous scale of the transformation that was taking place at that moment where the Western European working class was turned into consumers of a seemingly endless row of commodity objects from jeans to refrigerators to cars. Television has rapidly taken over mass communication at that time and the Situationist knew something was afoot. That they had to move quickly. The spectacle was a new phase of the capitalist subsumption of society. A historically specific accumulated production of images as well as one gigantic image of that whole mode of production in its total and complex structure. An image that had to be destroyed.

The notion of the spectacle was not intended as a narrow description of the new media of dissemination like television but as an analysis of a global totality in which new powerful means of communication were put to use including television but also cars, telephones, fashion etc. The spectacle was a form of domination that included consumption, mass media and politics where a torn capitalist world was held together by images-as-commodities and representations that colonized everyday life and the ability to understand everyday life. A new world was quickly being built on the ruins of World War Two in order to prevent another one from materializing. Debord was expanding Marx’ analysis of the exploitation of labor into a critique of the alienation of everyday life and communication and more or less all conceivable human activities including and not least art.

Art was of utmost importance for the Situationists. There’s no denying that. Debord has ended up in the art museum for a reason. It’s a tragedy, of course, but it was inevitable as long as we live in capitalist society Debord will be just one more rebel art commodity, a vedette if there ever was one. To Debord art was the promise of another world in this world. But it was already too late when the Situationists joined forces and sought to organize the revolution as artists. Art had been reduced to an accessory. Something nice to look at or something that could shock you. A provocation. But a provocation unable to fundamentally challenge anything. Just one more commodity.

Debord was a sophisticated analyst of capitalist society’s self-simulation in his time but he would probably be somewhat perplexed at the powerful emotion machines most of us use 24/7 today. iPhones, laptops, Facebook, Renren, Instagram, TikTok, you name it. As individuals of late capitalist society, we are accustomed from a really early age to live in a constant stream of visual imagery, constantly optimizing ourselves and our personalized extras, plastic surgery and Facetune (video link) ad libitum. An endless flow of images where we very rarely look at specific images for very long but just browse or swipe through the seemingly perpetual sweep of flickering optical appearances. If Debord thought of this as colonization, today it is a barrage or all-out civil war where we cannot not recognize ourselves through these visual stimuli. This is our world. Even more impoverished than the black and white clip Debord mockingly uses as the beginning of his film. The sequence lasts several minutes and is thus way too long when looked at from the perspective of today’s YouTube clips. It looks really handmade and still gestures towards some kind of radicalness, the transgressive potential of negation. Blank irony was still possible and carried a genuinely subversive dimension. Debord’s world was one of bookish discussions and radical gestures, or seemingly so, and the recuperation of these gestures, fake discussions and the integration of negativity. There was still a space for critique, doubt, hope, you could still distinguish between appropriation and recuperation, perhaps it was already too late for Debord, it probably was but the Situationists gave it one last go. The Situationist vanguard was in a hurry and had to move fast trying to outdo the spectacle, hit and run interventions like the one at Place Clichy in 1969 where the group placed a replica of Fourier on an empty plinth on the square trying to collapse the empty time of the spectacle connecting utopian socialism, the Commune and May ’68.

Today the colonization Debord witnessed is at an end and there are no discussions, no semblance of a public sphere, the notion makes no sense what-so-ever, there’s simply nothing to recuperate. Everything is already part of the spectacle. You can be an artist of international fame and pretend to be critical all the while making a mock-up Prada boutique with the help of Miuccia Prada herself in the desert in Texas or erect waterfalls in the harbor of New York or the park of Versailles. The evacuation of any semblance of criticality in contemporary art would be mind-blowing to Debord. It’s not even a question of pretending anymore. The high end of contemporary art has completely fused with the world of the super-rich or a bored global middle class.

The Fordist mass production that was remaking the world in the 1950s when Debord was drifting through Paris before it was completely remade has been expanded and become standardization with a difference. Dodging the secular stagnation that the old advanced economies of the West have been in for the last three decades goods are today made to fit the idiosyncratic preferences of ever-smaller groups of potential customers. There’s no difference that cannot immediately be satisfied. Accessories all over the place.

The imaginary and the real have fused, there’s simply no room between them, there’s nothing that cannot be translated into everything else. Debord’s irony is gone. The world of dialectics is no more. There’s no working-class anymore. In the sense of a force with a revolutionary potential subjected to the command of capital. Today ‘worker’ is an identity that channels hatred towards foreigners. Class struggle has become bad identity politics and the old political dichotomy of Left and Right has finally shown itself to be devoid of meaning, a holding pattern for the political spectacle of the old national democracies. Constant replacements and manipulations are the order of the day. Politics has been business for so long that the only possible opposition is a return to grotesque characters that present themselves as populist alternatives but only confirm the hollowness of the democratic institutions. Religious superstition and old forms of nationalism run rampant many places, not least the hurt hegemon of the US. But more or less everywhere the instant satisfaction of Facetune goes hand in hand with ever more empty references to national or religious communities. The spectacle 2.0 is the ideal setting for a sentimental re-enchantment of social relations.

If one was to approach present-day capitalist society with the revolutionary fervor of the Situationist one would be struck by the sheer stupidity of a popular culture where Kendall Jenner features in a Pepsi commercial as a wig-wearing Caucasian Black Lives Matter protester who hands a Pepsi can to a police officer. There’s apparently no end to the nightmare of a society where a general psychosociology replaces social being, where the subject has finally become a placeholder, a sum of representations that is purchased.