Taks, 1922. Carpet in wool, 182 x 128,5 cm. Ⓒ Holstebro Kunstmuseum

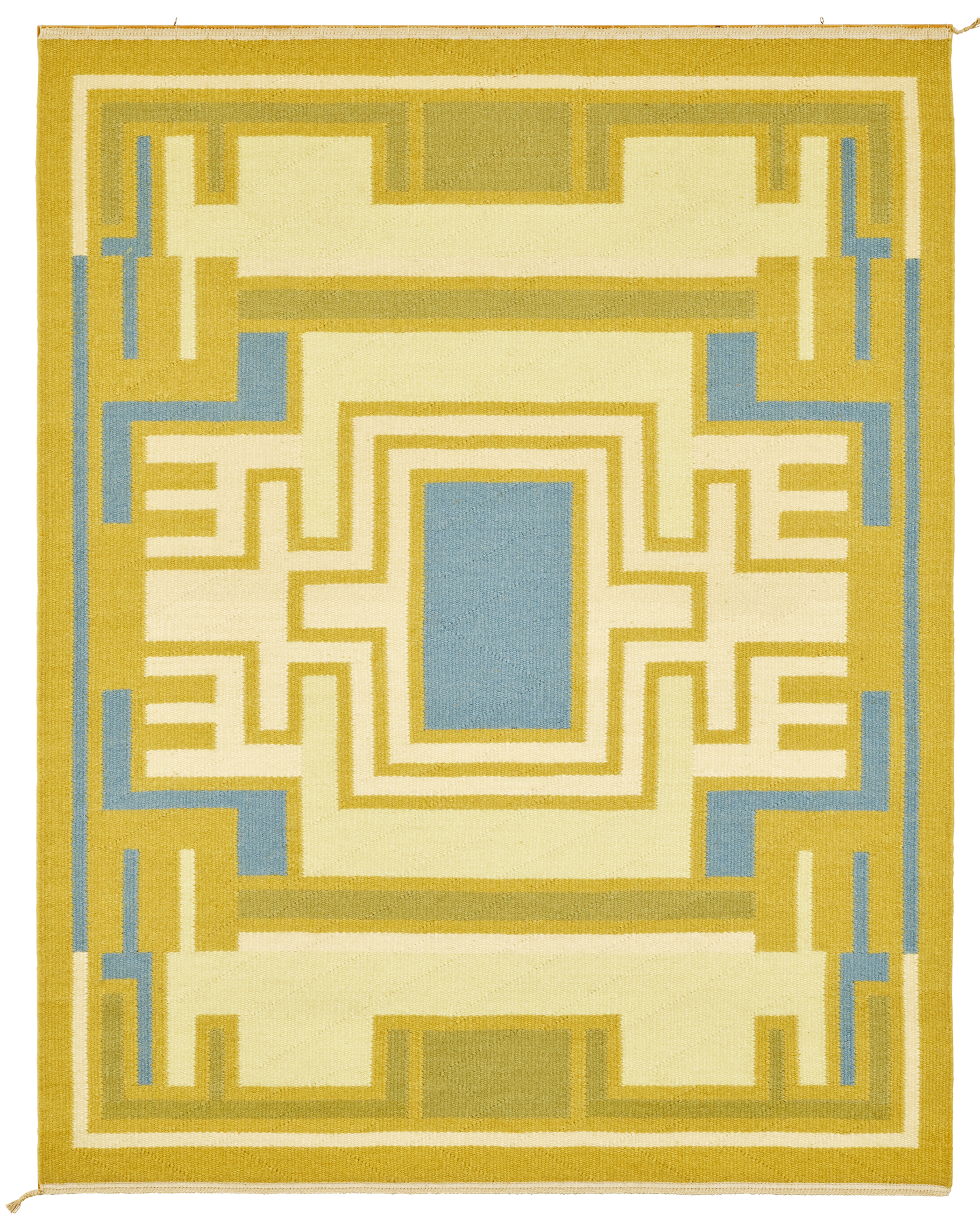

Taks, 1922. Carpet in wool, 182 x 128,5 cm. Ⓒ Holstebro Kunstmuseum Yellow, Blue, 1980. Carpet in wool, 161 x 126 cm. Ⓒ Holstebro Kunstmuseum

Yellow, Blue, 1980. Carpet in wool, 161 x 126 cm. Ⓒ Holstebro Kunstmuseum

Untitled, 1944. Carpet in wool, 170 x 111 cm. Ⓒ Holstebro Kunstmuseum

Untitled, 1944. Carpet in wool, 170 x 111 cm. Ⓒ Holstebro Kunstmuseum

Fall, 1995. Carpet in wool, 167 x 118 cm. Ⓒ Holstebro Kunstmuseum

Fall, 1995. Carpet in wool, 167 x 118 cm. Ⓒ Holstebro Kunstmuseum

Red and Blue, 1954. Carpet in wool, 175 x 134 cm. Ⓒ Holstebro Kunstmuseum

Red and Blue, 1954. Carpet in wool, 175 x 134 cm. Ⓒ Holstebro Kunstmuseum

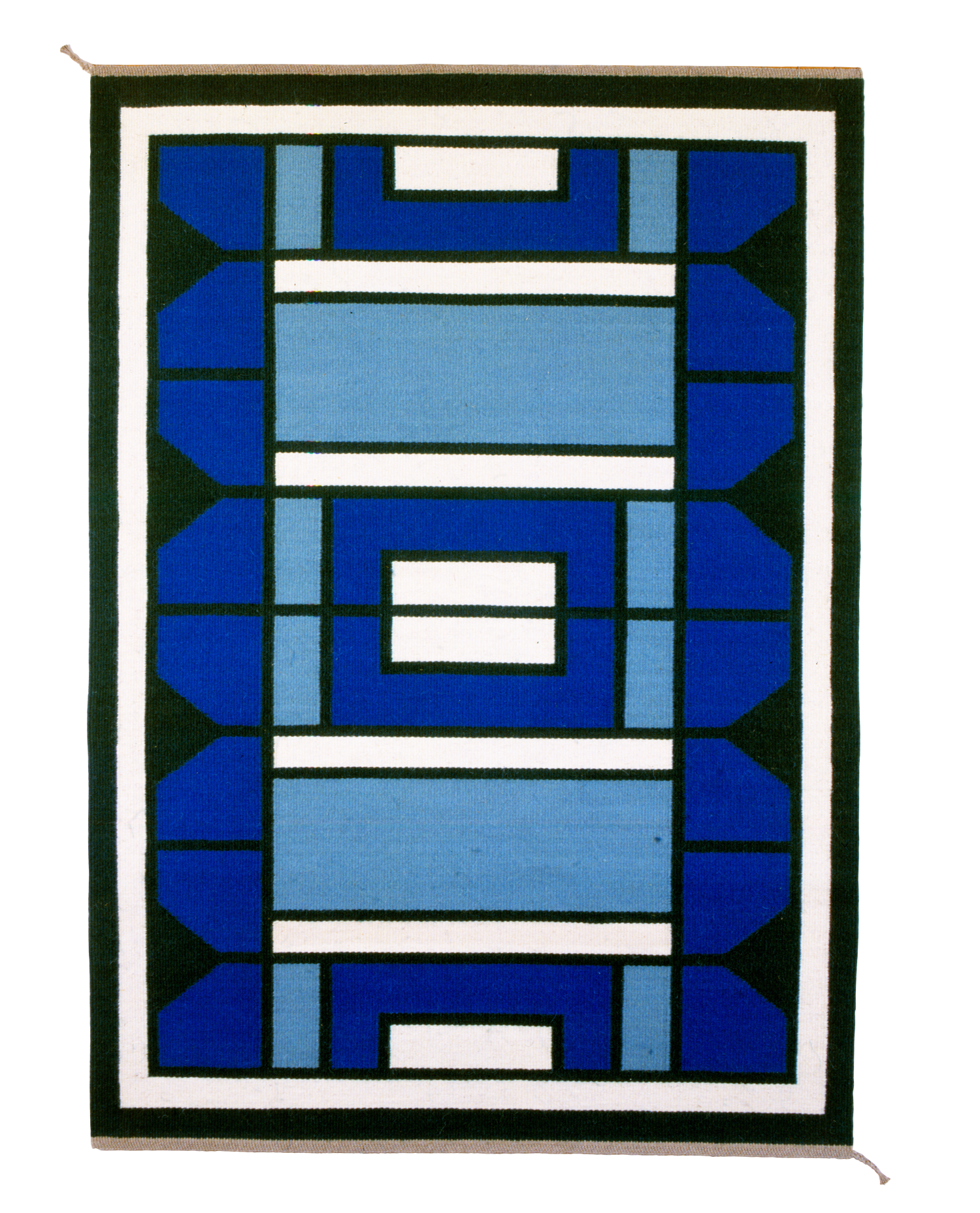

Untitled, 1978. Carpet in wool, 170 x 126 cm. Ⓒ Holstebro Kunstmuseum

Untitled, 1978. Carpet in wool, 170 x 126 cm. Ⓒ Holstebro Kunstmuseum

Red Image, 1983. Carpet in wool, 172 x 126 cm. Ⓒ Holstebro Kunstmuseum

Red Image, 1983. Carpet in wool, 172 x 126 cm. Ⓒ Holstebro Kunstmuseum

Untitled (commissioned for Nørreland school), 1968. Carpet in wool, 241 x 732 cm. Ⓒ Holstebro Kunstmuseum

Untitled (commissioned for Nørreland school), 1968. Carpet in wool, 241 x 732 cm. Ⓒ Holstebro Kunstmuseum

Carpets and art share a long and interwoven past. Historically there was no distinction between the two. Carpets have been a legitimate medium for both art and artistic expression, yet something changed in the western world during early modernity. Carpets have kept their status as valuable objects, yet they have lost their status as works of art, instead crossing over into categories of craft and decorative art. As a result of this “new” category for carpets and textiles in the art space, they now seem to possess a kind of otherness that, within an art setting, keeps them silent.

The Danish artist and weaver Anna Thommesen (1908-2004) was well aware of the category of her work when she started exhibiting in the early 1940s. Her first participation in a censored exhibition was in 1943 where she showed a rag carpet at Kunstnernes Efterårsudstilling (The Fall Exhibition) in the section called decorative art. Yet later in her career, she mainly exhibited with artists who were outside the context of handicraft or decorative art. Together with her husband, the sculptor Erik Thommesen, she was a member of the artists association Martsudstillingen with whom she exhibited from 1952 until the group dissolved in 1981. Martsudstillingen, meaning The March Exhibition, was named after the month it first took place but they soon came to exhibit regularly in January each year. It was a small artists association containing both abstract and figurative painters and sculptors, as well as Thommesen who worked in textile and the ceramic artist Gertrud Vasegaard. Within her own circle of colleagues, Thommesen was regarded as an artist in her own right and exhibited her works alongside their paintings and sculptures without any formal distinction between artworks. This makes Thommesen’s exhibition activities with Martsudstillingen an interesting case study, and begs the question - how was this setting of her work received by the public?

A rich source to explore this question are the reviews published in daily newspapers of the annual and later bi-annual exhibitions staged by Martsudstillingen in Copenhagen between 1952 and 1981. The group of artists that made up Martsudstillingen were highly esteemed and greatly respected, especially in the 50s and 60s. Compared to most of the other artists associations at the time, Martsudstillingen was far smaller with only 11 regular members, all of whom shared a common understanding of art. This sat Martsudstillingen aside compared to the other, much larger artists associations, who’s annual exhibitions sometimes could have the aura of being artist organized art fairs. Up until the mid 70s Martsudstillingen was widely reviewed in most major Danish newspapers, and the reviwes were often long and detailed.

What is striking when you go through these reviews is how little Thommesen is featured. The absence of actual analysis of her work is remarkable compared to the volume of texts and reviews, especially considering the size of the group which most years had no more than 10 members exhibited. Visually, Thommesen’s works were often very prominent in the exhibitions - her wall-hung weavings almost always outsized most of the painters in the exhibitions who predominantly preferred to work on a smaller scale. Nonetheless,the painters in the exhibitions would always get the most attention from reviewers.

In 1961 Martsudstillingen celebrated their 10-year anniversary. Thommesen joined the association in 1952, the year after it had been founded and had its first exhibition. For this exhibition, the artists did not necessarily show their latest works, but instead showed both new and older works. Thommesen participated with nine wall-hung tapestries, the smallest measuring 150 x 100 cm and the biggest 243 x 288 cm, produced between 1948 and 1960. From the list of works in the printed catalogue, it was possible to see that the carpets belonged to a number of prominent people. One had been given as a gift to the Danish King by personal friends, one belonged to the founding director of Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, Knud W. Jensen, another belonged to the director of Design Museum Denmark, Erik Zahle. This is of course no artistic accomplishment in itself, but facts that would normally draw attention to the artist. In the review by art critic Jan Zibrandtsen for the newspaper Berlingske Tidende, Louisiana Museum of Modern Art is mentioned but not in connection with Thommesen’s carpet. Instead, Zibrandtsen focuses on the museum buying Erik Thommesen’s sculpture Woman (1960) which, according to Zibrandtsen, must be regarded as one of Erik Thommesen’s masterpieces. (1) About Thommesen Zibrandtsen writes, “by combination of Anna Thommesen’s lovely plant-dyed carpets and Jeppe Vontillius’ landscape paintings and model studies a remarkable artistic effect has been achieved in one of Den Frie’s round exhibition halls.”(2) This is all he has to say about Thommesen’s work, while he later comes back to elaborate on Vontillius’ paintings.

Another example of the same striking silence about Thommesen’s art is found in a review from 1959 which ends with the sentence, “….and woven carpets by Anna Thommesen in plant dyed yarn.”(3) This mere description of Thommesen’s work is typical of the reviews of Martsudstillingen’s exhibitions. There are examples with slightly more description and comments, typically her colour combinations are seen as refined and described as very Nordic and typical for Martsudstillingen as a group.

Though Thommesen’s work didn’t get much attention in reviews, it doesn't seem as though the writers disliked her work. In their sparse remarks, reviewers tend to be positive, but they offer no real insight or artistic evaluation. One reason for this could be that the critics had no or very few references of comparison. In a few reviews, Thommesen’s works are put in relation to “Indian carpets” and “folk art,” but these references remain more like descriptions of her work rather than tools to analyze it. In three different reviews, Thommesen’s art is described in more or less the same manner; “a delight for the eye,”(4) “lovely to look at,”(5) and as “peace and quiet for the eye.”(6) In the same three reviews, the critics refer to several other artists when they write about the painters participating in the exhibitions. In the paintings they see references to the Danish painter Harald Giersing, Cezanne, Corbet, Constable og Wols (Alfred Otto Wolfgang Schulze), while all there is to say about Thommesen is that her carpets are lovely to look at.

The critics’ lack of context and meaningful references in connection with Thommesen’s art could be to blame for this missing interpretation of her work. The lack of context is also directly linked to the little context that is given, such as folk and tribal art. Folk and tribal art can be understood as obstacles for further analysis and contextualization. These references have strong communal connotations, which make the art associated with such references fit badly within the modernist conception of art highly connected with individuality. This leads to the silence surrounding her work whilst adding an otherness to it. Why and how this communal reference is an obstacle for the modernist concept of art can be observed in a few texts about Thommesen outside of the reviews of Martsudstillingen’s exhibitions.

The Danish writer and art historian, Poul Vad, is one of very few who has written about Thommesen’s art outside the daily press. One example is in a short catalogue text in connection with an exhibition with Thommesen and her husband in 1985. In this essay, Vad remarks that Thommesen’s art reflects an artistic personality and contains something anonymous. These two polarities are connected to art on the one side, and craft on the other. Vad writes, “There is and has always been an element of anonymity in good craft. Weaving as well as ceramics has their origins in plain craft, and even in the most refined forms of these, which bear the mark of a great creating personality, is the medium’s inherent order respected.”(7) What can be deduced from this is that craft, because of its connection to applied art, always contains a certain loyalty to the medium’s essence or inner character - be it weaving or ceramics. This loyalty is what gives Thommesen’s art it's anonymous expression in general, while her use and combinations of colours and her compositions give her art its own personal language.

What is interesting in Vad’s text is the assumption that weaving, and mediums connected to craft in general, is understood as bound to the specific medium’s essence in a higher degree than the mediums of painting and sculpture.(8) This is a clear cultural cliché that reflects a western and modernist understanding where painting is seen as the freest form of art. Further down in value are mediums with a historical connection to craft and applied art in which it is supposedly perceived to be more difficult to make any kind of individual or free expression. In Rozsika Parker’s book The Subversive Stitch from 1984, she argues that this understanding is detectable from the renaissance, where embroidery lost the battle against painting and its exclusion from fine art began. Parker argues that, while it is normally understood that embroidery’s downfall happened because it was not technically able to render the same level of naturalism as painting, the actual cause was a change in the understanding of the artist’s role and new values put into this role. One of these new values that the artist should possess was a certain level of ease or naturalness. The artwork should also emit this ease or lightness, which also meant it should express a kind of quickness of speed that the embroidery could not convey in a convincing way.(9)

The lack of criticism of Thommesen’s art reflects a modernist attitude towards what art is; which requires an individual artist from whom the artwork must stem and express the individuality of the artist. In another book by Parker which she wrote together with Griselda Pollock, Old Mistresses from 1981, they exemplified this need for individuality in art with a quote from a review of a 1974 exhibition in London of woven blankets by American Navajo women. Parker and Pollock quote poet and critic Ralph Pomeroy:

“I am going to forget, in order to really see them, that a group of Navajo blankets are not only that. In order to consider them, as I feel they ought to be considered – as Art with a capital ‘A’ – I am going to look at them as paintings – created with dye instead of pigment, on unstretched fabric instead of canvas – by several nameless masters of abstract art.”(10)

Parker and Pollock expand upon the quote:

“Several manoeuvres are necessary in order to see these works as art. The geometric becomes abstract, woven blankets become paintings and women weavers become nameless masters. This term is crucial. In art history the status of an artwork is inextricably tied to the status of the maker. The most common form of art historical writing is the monograph on a named artist, often supported by a catalogue raisonné of all the paintings and drawings so that a group of works is given coherence because it is seen to issue from the hand of an individual. (…) Thus in order to give the final stamp of approval to Navaho products as art, Pomeroy conjures up ‘nameless masters’, a phrase which echoes that used by modern historians to create an artistic identity for an artist whose name has become lost to history.”(11)

As Parker and Pollock’s example shows, an artwork needs an individual maker. This is not a conception that has been formulated by modernism alone, but reflects an understanding of the artist’s role conceived in early modernity and solidified in both the enlightenment period and through the Romantic era’s notion of the artist genius. The Romantics saw the artist as a singular prophet-like person, with a special ability to see beyond the shadow images we normally experience in our daily life. The Romantic artists’ work therefore reflects a higher truth and offers normal people a glimpse of this. This understanding of the artist’s role leaves very little, if any, room for communal work or practice. It is required that the work comes from a singular,special person.

In regard to Thommesen, it is ironic as she worked completely alone and in theory, fulfilled all the romantic/modernist requirements for how an artist needs to work. Thommesen never said very much about her own art or how she understood the role of the artist, but from the interviews she gave and the few arts-related discussions she was involved in, it is clear that she had a romantic/modernist view on art and the artist’s role herself. To Thommesen, this understanding of art and weaving did not represent a conflict, but the silence her work was met with indicates that it did represent a problem in the eyes of the critics. As discussed above, weaving is understood as a medium with limited possibility to express individuality. This is related to the medium’s historical connection with craft and applied art and these categories’ affiliation with tradition and communal work, which has led to its exclusion of fine art through western modernity. This seems to be a self-reinforcing structure, which ends in the assumption that weaving overwhelmingly expresses tradition and craft instead of individual artistic genius. It is this perceived lack of individuality that induces an otherness into carpets when brought into the white cube.

This structure becomes evidently absurd if we consider a number of the artistic movements that have come to define what we today call contemporary art such as minimalism and conceptual art. Both are movements or practices where it is often a direct point that the artist has not touched the actual work, but merely picked something out or made up a set of rules to generate the artwork. This chosen, non-individual method has nonetheless not left critics without things to say about these artworks and artists. Think about the quantity of books written about artists such as Donald Judd, Carl Andre, and Joseph Kosuth. It can be argued that both minimalism and conceptual art are movements with a wish to nihilate or at least question the position of the artist. A true rewriting of this position or role has not been accomplished, most likely because of the art market and this market’s affiliation with the romantic/modernist understanding of the artist. Nothing is more lethal to the value of an artwork than doubt about its authorship. Value, the art market, and a romantic/modernist concept of artistic individuality are part of a structure that has shown itself to be extremely resilient and has survived decade-long attacks from different artistic movements questioning it. Most often, the critic of this structure ends up being absorbed by it and can do extremely well financially working inside the structure.

Again, it is ironic, that whilst the mentioned American white male artists’ practices can be said to question the romantic/modernist conception of the artist, Thommesen didn't. For the art market and its structure, it seems as if it is easier to overcome and absorb criticism of itself, than it is to absorb a medium not associated with the required artistic individuality, however arbitrary this association might be.

When it comes to carpets and their otherness in connection to art, it is also important to draw attention to gender and the general association between weaving and female labour. This is obviously a major factor in carpets’ otherness, if not the most significant part, from which the other mentioned factors originate, combine and interconnect. Weaving is both seen as a medium lacking individuality and a medium connected to communal work, and both can be connected to a general idea of femininity. These three factors together are what gives carpets and weaving their otherness when seen as art. In Thommesen’s case, this otherness did not lead to condemnation or negative criticism, but to silence and blocked analysis of her work. The lack of analysis and artistic context that this silence has led to is most likely one of the main reasons why Thommesen is now only known to a very specific audience with either a niche interest in textile or the artists associated with Martsudstillingen.

In my own experience, the silence that Thommesen’s work was met with is still not uncommon today when art assimilates items or styles traditionally connected with craft and applied art. It is extremely important that we consider where this silence comes from, and the preconceptions such silence represents. The silence presumes that there is nothing to be said, because the object in question is mere decoration and surface with no artistic depth or meaning. This would as such not be a problem, if this didn't also imply a gendered imbalance. Historically as well as today, mediums associated with female labour are often met with what I have called a romantic/modernist view, discrediting the work, because according to this understanding the work lacks the individual artistic expression needed to create an artwork.

1) Jan Zibrandtsen: ”Den menneskelige betoning”, in Berlingske Tidende 22.01.1961

2) Jan Zibrandtsen: ”Den menneskelige betoning”, in Berlingske Tidende 22.01.1961

3) Svend Eriksen: ”Let fransk køkken” in Dagen Nyheder d. 24.01.59

4) Bertel Engelstoft: ”Ærlighed og poesi” in Information d. 26.01.57

5) Pierre Lübecker: ”Den stille skønhed” in Frederiksborgs Amts Tidende d.02.05.52

6) Leo Estvad: ”Der er så tyst derude” in Berlingske Aftenavis 02.02.63

7) Poul Vad: ”Anna Thommesen” in the exhibition catalogue Anna Thommesen, Erik Thommesen published by Kunstforeningen, 1985, s. 7

8) I find it important here to stress that even though Vad expresses a view of weaving that I find obsolete, Vad is one of the few critics who does have something to say about Thommesen’s art. He is as such not silenced by the presumption that weaving expresses individuality badly.

9) Rozsika Parker: The Subversive Stich, Bloomsbury, London and New York, p. 79-81

10) Ralph Pemeroy: ”Navaho Abstraction” in Art and Artists, 1974, p. 30 here quoted from Parker and Pollock: Old Mistresses, Pandora, London, Sidney, Wellington, p. 68

11) Rozsika Parker and Griselda Pollock: Old Mistresses, Pandora, London, Sidney, Wellington, p. 68-69

Image Proveniens: Holstebro Kunstmuseum