‘Love Saves The Day’ by Tim Lawrence, courtesy of Duke University Press

‘Love Saves The Day’ by Tim Lawrence, courtesy of Duke University Press

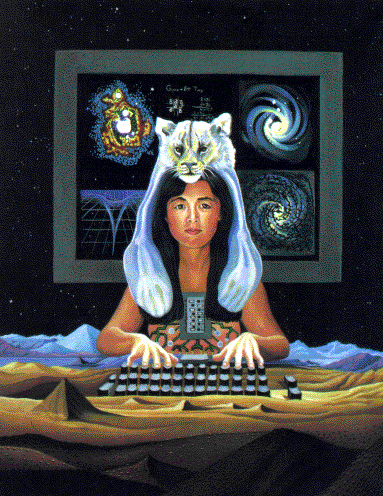

Donna Haraway ‘A Cyborg Manifesto’

Donna Haraway ‘A Cyborg Manifesto’

Disco is not merely a genre of dance music, but a complex subculture holding progressive political beliefs. Alongside it’s glittering clothes and sexy moves, disco came to rise in the United States in the 1970s, evolving from the well-known international sounds of Motown, rooted in New York and Philadelphia.

The term disco derives from the French word discothéque, meaning ‘library of phonograph records’. During World War II, it was illegal for live bands to play in France and in response the discothéque was invented. Disco came to England and the United States in the 1950s, and in the 1960s disco gradually came to describe not just the dance clubs where records were played instead of live music, but the entirety of the disco-subculture.

The Stonewall Riots were a series of demonstrations taking place in Greenwich Village in New York in the Summer 1969. Following a police raid at the gay bar, Stonewall Inn, many people gathered in the streets to fight back against the police brutality. The Stonewall Riots became the starting point for LGBT rights and the gay liberation movement and a momentous starting point for the disco-era. Disco may not have reached the same cultural reverence as Rock’n’Roll or Punk, but its revolutions have been far-reaching nonetheless.

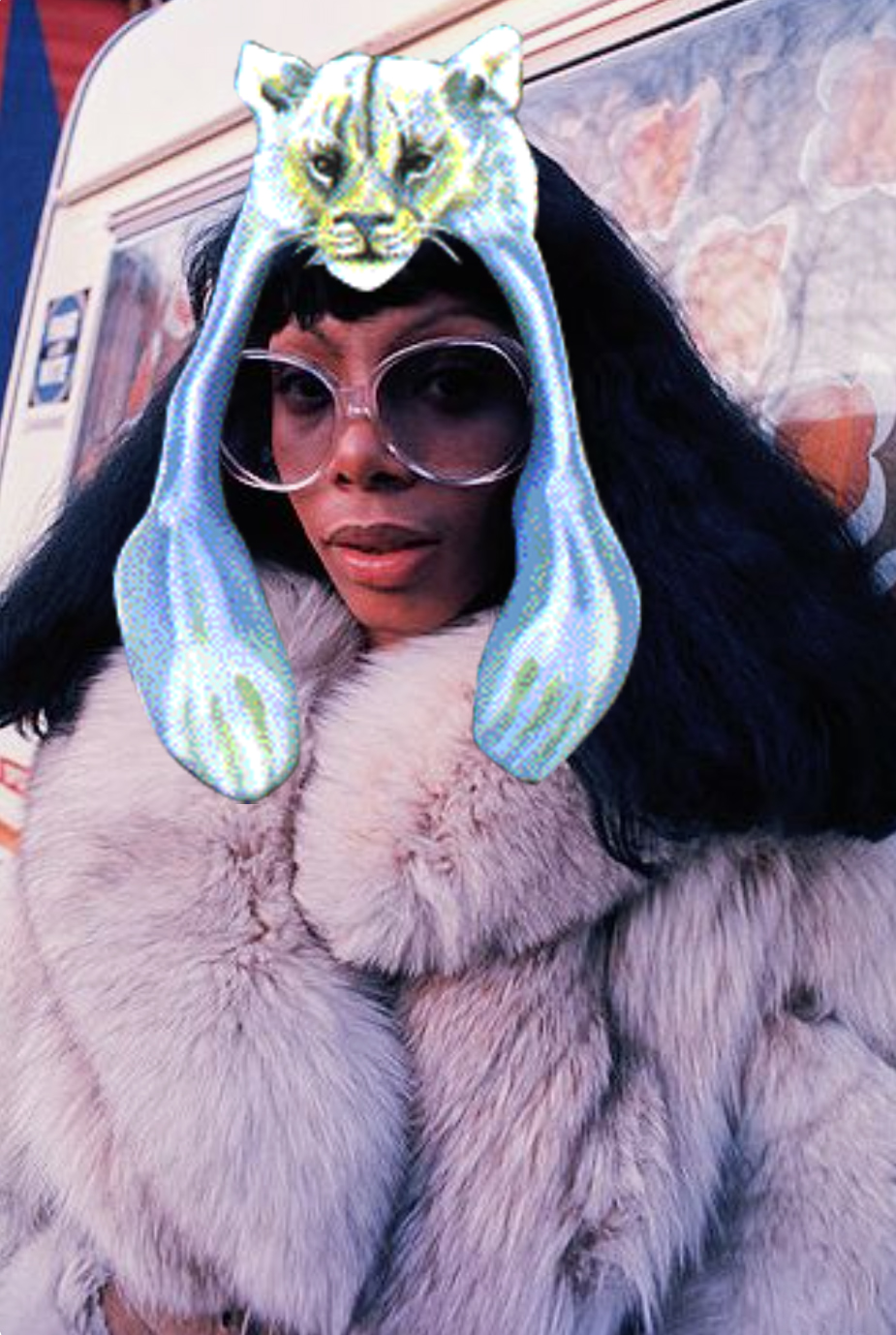

During the 1970s, numerous disco night clubs appeared in New York such as the infamous Studio 54, The Gallery and The Lofts. Professor Tim Lawrence writes in his article ‘In Defence of Disco (again)’ that even though disco became mainstream and commercialized during the 70’s, it mirrored the folk and rock movements of the 60’s. Lawrence argues that disco suffered because it had fewer allies in the major record companies, whose ranks were dominated by straight white executives. They were more on side with the rebellious postures of the Rolling Stones and Bob Dylan rather than the gutsy emotional outpourings of the black female divas of Gloria Gaynor, Loleatta Holloway, Donna Summer and Grace Jones.’(1)

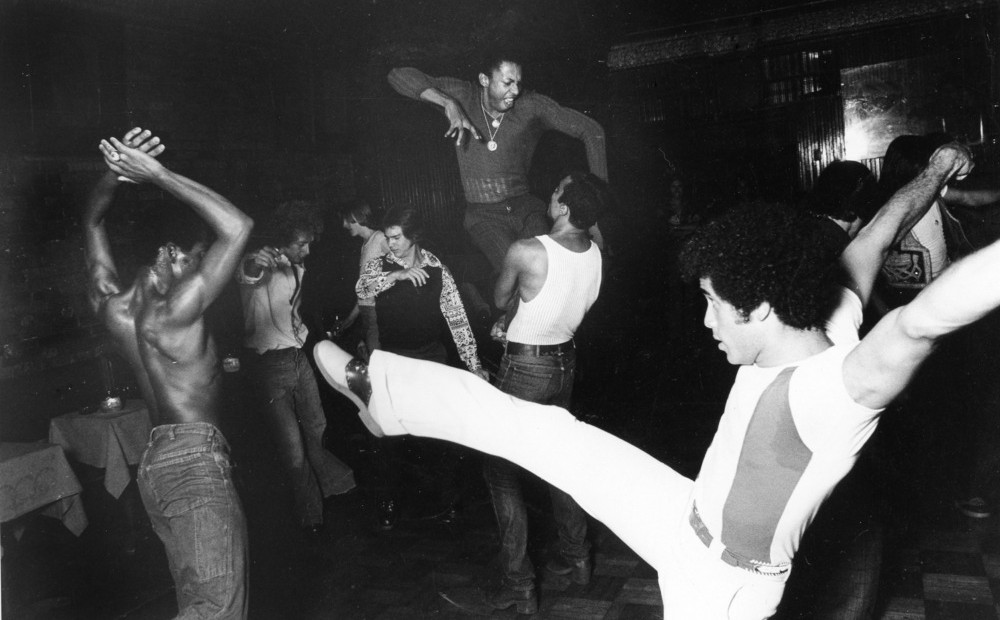

Until 1971 it was illegal for two gay men to dance with each other, but disco disrupted thischanged that. Disco changed the way people moved as the dance floor was no longer restricted to straight couples. Disco was a revolution. Disco music was the perfect medium to foster a sense of togetherness through diversity and this new crowd changed the structures of social dynamics through the dance floor. I was in these dynamics and energy brought about by the rhythms in disco that enabled a range of minorities - female, gay, black and latin people - to be able to define their identities in increasingly fluid ways.

‘It unites the whole audience when you have 100 people singing along on the dancefloor. It becomes divine: a love epidemic’ explains Nicky Siano, a former resident DJ at the legendary club Studio 54 in New York back in the heyday of disco.(2)

Disco not only increased the diversity of the crowd that found their home in dancing to the music, it also made it easier for female, gay, black and latin artists to express themselves. Disco’s primary voice was female, or at least not conventionally male, and there are several examples of using disco as a means of empowerment. One of the most striking examples is Gloria Gaynor’s hit ‘I Will Survive’ from 1978 which was embraced by the LGBT community. A black female in the spotlight expressing strength, independence and power was both new and highly empowering to everyone struggling in society. A symbol that if she can do it, we can do it.

Disco singer, Jocelyn Brown, confirms this feeling that ‘for Brown, disco represented a certain empowerment; she was no longer asked to ‘tone down’ her vocals to make them more ‘radio-friendly’, and she ensured that her presence was felt (‘I’ve been blessed to keep myself in check; I’m a respectable black woman, and you know you have to respect me’). At the same time, it grew clear that money men ruled the industry.’(3)

1977 was an important and transitional year in the disco-era. The most infamous disco club, Studio 54, opened in New York, the movie Saturday Night Fever and Donna Summer and Giorgio Moroder’s hit ‘I Feel Love’ were both released.

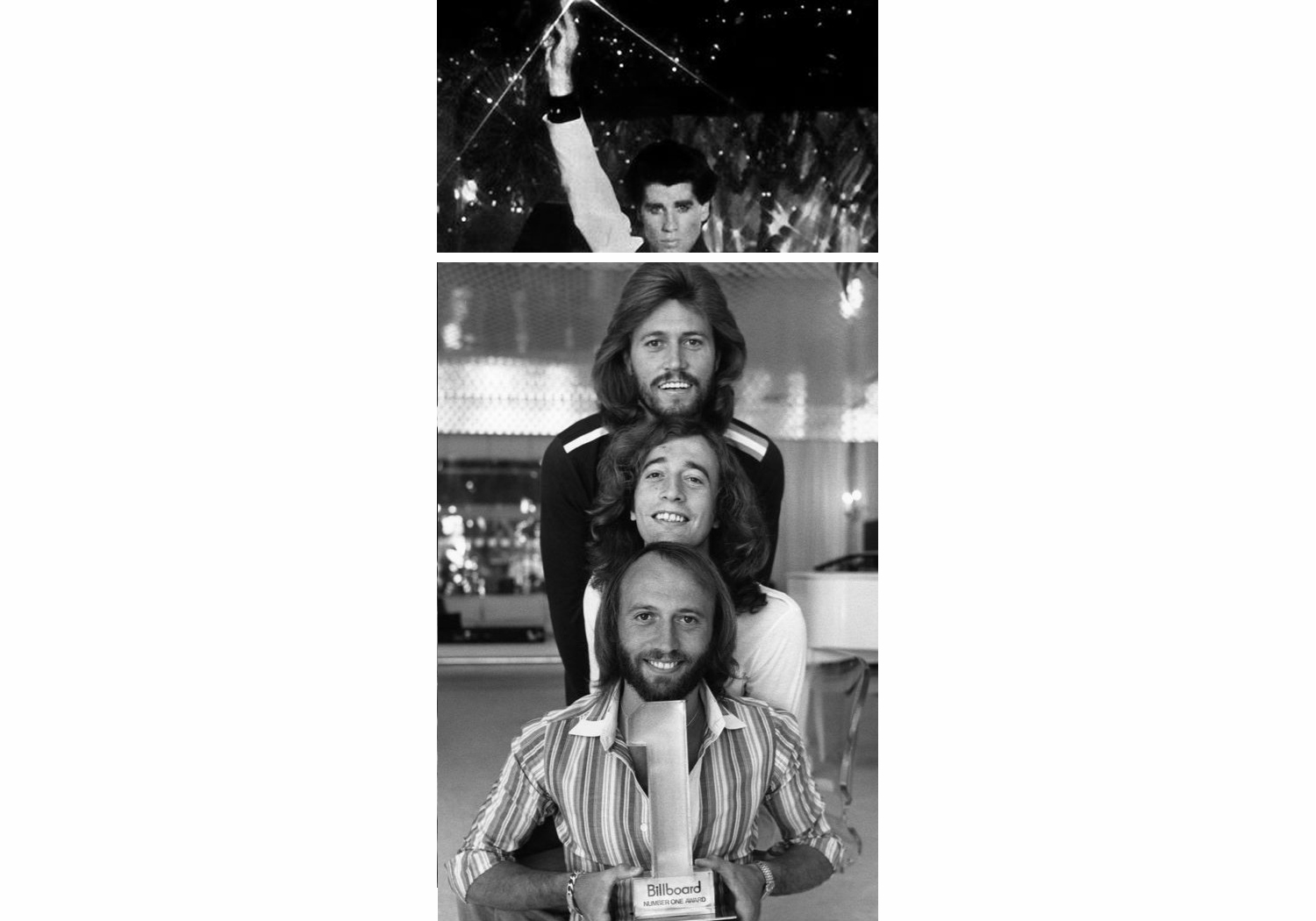

However, Saturday Night Fever was not in line with the beliefs and values that had been connected to the Disco-movement so far. John Travolta, the epitome of a privileged white male, showed incredibly hetorosexual dance moves in his performance of a Italian working class man... One could wonder what were the motives behind this movie? The film can be seen as in no way embracing the minorities that created it in any way, and if anything, the film subverts the very essence of disco. The film was a clear commercialisation and political move to reappropriate disco as accessible and acceptable to a mainstream, white market. Through the main character Tony Manero, played by John Travolta, disco was reframed and presented as being a beacon for patriarchal masculinity and heterosexuality.

A main trait in disco culture was its openness to everyone, no matter what their sexuality, race or gender and that they could enjoy themselves on the dance floor no matter who they were. But in this commercial approach and with the intense focus on the prestigious disco clubs like Studio 54, the dance culture in the clubs became further driven by aesthetics. The door policy at the clubs moved from inclusion to exclusion and humiliation. Famous and good-looking people were let in, and the dance floor became a place to show off, regressing to becoming a space for heterosexual couples like those in Saturday Night Fever.

This political twist in the representation of disco became even more apparent in the soundtrack to Saturday Night Fever. Famously made by the Bee Gees: a white male band, they were further renowned for never having heard the term disco before whilst scoring the music to the film.(4) The music by this popular, mainstream band gave the audience the impression that disco was just a continuation of many of the values that formed white America, in spite of the reality that the vast majority of disco musicians were black.

Tim Lawrence argues that the appropriation of disco from black to white may not have mattered if the film had not been such a commercial success. As a result, the majority of people saw the film as the initiation of disco with no knowledge of it’s real history. Sadly, this false narrative killed the real disco culture as it became overexposed, cheapened and over the top in the mainstream changing how disco is historically seen.

Going back to 1977, ‘I Feel Love’ by Donna Summer and Giorgio Moroder in comparison to Saturday Night Fever comes from a completely different world. Professor Tilman Baumgärtel describes the song as ‘alien and futurist,’(5) a description that still stands decades later.

Donna Summer was born on New Year’s Eve in 1948 in Boston and moved to Munich, Germany in 1968 to participate in the German edition of the musical Hair. Before, she had already been singing in a band called Crow. In 1973, living as a single mother in poverty, she responded to an advertisement for a black female singer and signed to Giorgio Moroder and Pete Belotte’s label, Oasis, the following year.

Both Summer and Moroder can be viewed as transnational artists since they both were German and non-German at the same time. Donna’s father had been stationed in Germany and taught Donna’s mother German. Donna had lived in Germany for six years between 1968 – 1975 where she married and divorced the Austrian Helmuth Sommer, from whom she took her stage name, Summer. Yet Donna’s dubious nationality and Afro-German identity was often held against her.

Many Afro-Americans felt that her marriage and absence from the states made her less of a representative for the Afro-American community. As noted by author Josiah Howard, she was considered only as an ‘acceptable’ black performer by the African-American community and that has long since overshadowed her career. Looking back, it’s a shame that she hadn’t been embraced and praised by her community for being a strong independent black woman.

In addition to the question about her racial and national affiliation, people questioned her sexuality and there was rumour that she was transsexual. This, together with how she performed and how the electronic composition of the track was groundbreaking, put Donna in some sort of liminal category with a mysteriousness around her that made her hard to define.

It is important to stress that Donna herself was acutely aware of how she represented herself in her performances, borrowing from the identities learnt from her roles in musicals. Donna said, ‘I don’t think a lot of people understand where I’m not an artist that’s trying to establish style. I am an actress who sings, and that is kind of how I view myself. Whoever the character is in the song, that’s who I try to become.’(6) She made her identity fluid as a way of working against the norms of society and as a way of liberating herself. Summer’s chameleon-like identity can be seen as a practice of empowerment and a resistance to being controlled by societyin relation to what Darlene Clark Hine has called black women’s ‘Culture of dissemblance’ as a direct result of slavery, suppression and rape.(1) Donna took control of her sexuality and persona as a black woman and could not be categorised.

(1) Professor and a leading historian of the African-American experience who helped found the field of black women’s history.

‘I Feel Love’ is considered to be the first disco track produced entirely by electronic means (except for vocals and bass drums), seen as the inspirational precursor for the developments of House and Techno music. The electronic sounds from the Moog synthesizers used by Moroder gave the song a highly futuristic feeling that made it groundbreaking and alien. It became a global hit in the year of the release and it is still a famous dance track at both family parties and techno raves.

Even before it’s mainstream success the track was a hit in many gay clubs. ‘I Feel Love’ is the perfect symbiosis of organism and technology, human and machine. Music journalist Peter Shapiro called ‘I Feel Love’ a masterpiece of mechanocroticism and compared the song to Donna Haraway’s notion of the cyborg, that with ‘ songs like this… disco fostered and identification with the machine that can be read as an attempt to free gay men from the tyranny that dismisses homosexuality as an aberration, as a freak of nature.’(7)

Donna Summer’s comparison to Donna Haraway’s cyborg is unavoidable. Professor Donna Haraway wrote ‘The Cyborg Manifesto’ in 1985. For Haraway the cyborg is a future creature of a world without gender, an artificial being that has no gender, race or sexuality. When performing ‘I Feel Love’ Donna Summer becomes such a cyborg in Haraway’s notion of the term. She can’t be put into the boxes that society wants to put her in. Donna Summer turned knowingly away from the qualities usually attributed to her ethnicity as well as her gender in a way that Donna Haraway might have approved.

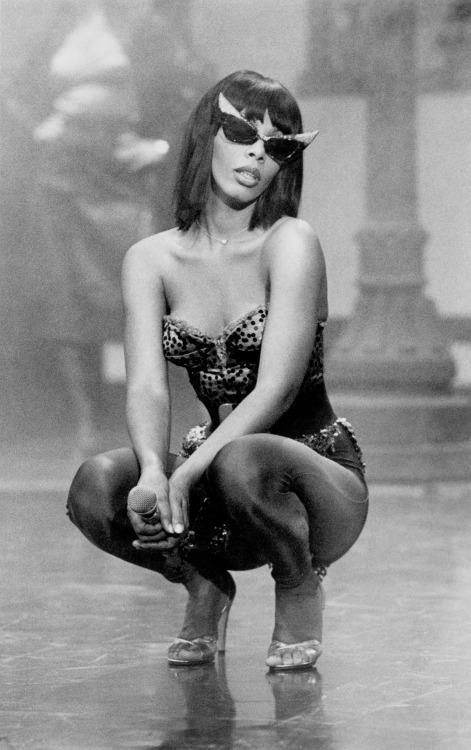

It was not only the futuristic and electronic sound of ‘I Feel Love’ that cultivated the sense of a man-machine symbiosis, but also Donna Summer’s highly robotic dance moves when she performed the song live. Comparing these different elements and perspectives from Donna Haraway, Darlene Clark Hine and Peter Shapiro, this robotic or fluid personality is similar if not identical to what is now known as an afrofuturistic personality.

Afrofuturism uses the narrative practice in science fiction to write the future as black, and as Lisa Yaszek writes, ‘‘I Feel Love’ does just the same – and this time the face is female.’(8) Donna Summer’s dance movements shift between the passion and seductiveness of the human in flesh and blood with the robotic mechanical movements similar to that of electro-boogie dance. In these instances, Donna has been compared to the artificial Maria from Fritz Lang’s movie Metropolis – a robot that looks like a woman. And this is also the occasion when Peter Shapiro called her a Teutonic Ice Queen, which somehow embodies the German characteristics as well as the robotic movements.

The man-machine aesthetic had already been introduced by German Kraftwerk who released the internationally famous record Autobahn in 1974 and had been a huge inspiration for Giorgio Moroder. The American professor in African Studies, Tricia Rose, believes that the reason why many artists especially from the Afro-American community took on robot aesthetics was somehow a shield or a protection, adopting ‘the robot reflected a response to an existing condition: namely that they were labour for capitalism, that they had very little value as people in this society. By taking on this robotic stance one is ‘playing with the robot’. It’s like wearing body armour that identifies you as an alien: if it’s always on anyway, in some symbolic sense, perhaps you could master the wearing of this guise in order to use it against your interpolation.’(9)

The disco-era started and ended with a riot. The night that disco died took place on 12th July 1979 where Chicago rock radio host Steve Dahl (known for hating disco) detonated forty thousand disco records in a hate party at Comiskey park. Dahl admitted that he didn’t hate the music as much as he hated the culture: ‘the backlash was anti-gay, but also anti-woman and anti-colour’ he says, ‘it was: Men, take back your power.’

Steve Dahl’s actions embodied the viewpoint of the New Right, the men that felt hurt that as white males they were not at the centre of this new popular music culture. They threw their alienated anger at all the groups that constituted the disco culture like homosexuals, women and people of color.

Disco died, not just because of the riot in Comiskey Park, but because it became over-commercialized, and it became equal to the bad taste of the 70’s.

Disco may have died,, but the beliefs and politics of disco lives on in House and Techno music. ‘The status of disco has shifted considerably and the genre, somewhat surprisingly, has now acquired the aura of an undervalued cultural formation that is rich in musical material and political example’.(10)

Disco has had an incredible influence on our culture and society, and disco should be remembered for what it is and always was meant to be about - love and equality.

And on that note:

Oh no not I, I will survive

And as long as I know how to love, I know I'll stay alive

I've got all my life to live

And I've got all my love to give

And I'll survive

I will survive

I will survive

(Gloria Gaynor, I Will Survive, 1978)